steven asquith: analogue pictures

21.12.23 - 27.01.24

Steven Asquith / analogue pictures

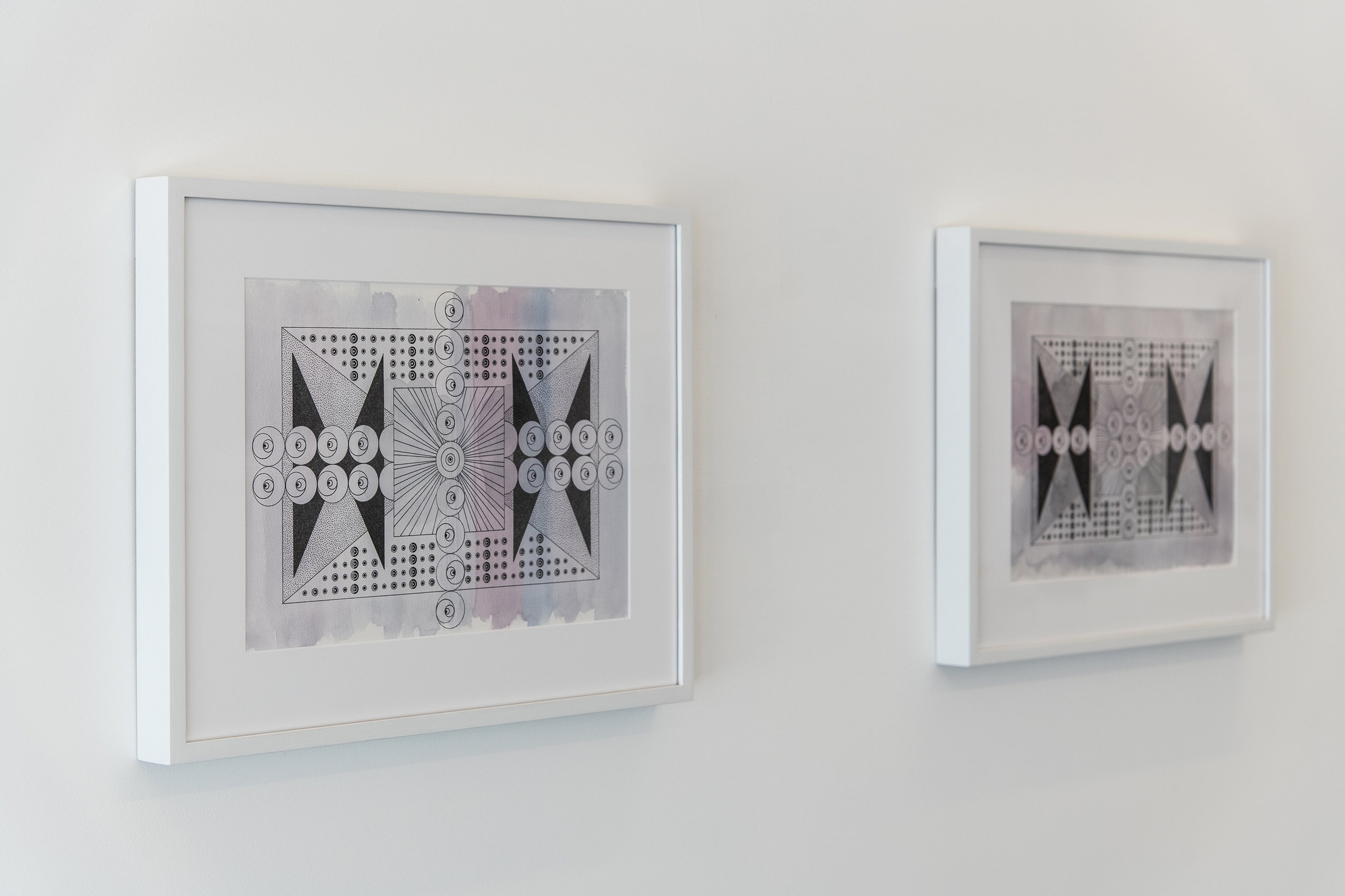

As a sequence of hieroglyphs that line the gallery walls, Steven Asquith’s new series of works on paper, Analogue Pictures, represent abstract narratives that attempt to unravel the current global diaspora and the circumstances and events affecting us all today. But unlike the ancient hieroglyphs that depict a literal representation of events or stories, the imagery in Asquith’s works forms an abstract language and gestures to our inner response to the events of today and our recent past.

Analogue Pictures continue Asquith’s exploration of abstract narratives that engage with psychological states derived from contemporary narratives. The layered and intricate works are fine representations of Asquith’s concern with the multi-layered meanings that images encompass. A point of departure in this enquiry is the numerous definitions of the term analogue in the exhibition's title.

Analogue can signify the information or signals represented by a continuously variable physical quantity such as spatial position; a contrast to the digital and technology; signify a person or thing seen as comparable to another; a clock or watch showing the time by means of hands or a pointer rather than displayed digits; analogue sound machines; repetitive patterns. In Chemistry, an analogue is a compound with a molecular structure similar to another. We can consider an analogue to be something similar or comparable to something else, in general, or in some specific detail—something analogous to something else. These varied connotations suggest a polysemous lens with which we should approach these works.

At first glance, the series of 20 works on paper seem identical. However, upon closer examination, we notice the restrained variances in each. Take for instance, the watercolour underlay in each work. Each portrays contemporary skyscapes affected by smog or cloud formations at urgent times of the day. Here Asquith alludes to the traditions of the landscape, although these are rendered with an allusion to the real threat of global warming and climate change. The epoch of these works is contemporised in reference to the most significant issue affecting humanity's future: our reliance on fossil fuel economies and that our dependency needs to be addressed. Fast. And although this observation is apparent, it is only one of the many implications of the work.

Next, we look to decipher the other abstract icons in the works. Familiar abstract tropes and shapes —squares, triangles and circles—reveal diverging patterns across the surface of the works. How they are composed and repeated allows us to grasp the differences.

Abstractions resonant of eyeballs appear to rush across the surface of the works at speed and in patterns, each more abstract than the last. Vertical and horizontal compositions emerge. At times circling out from the centre of the image, appearing as a sacred space meditation mandala. However, these meditations are present as a spiritual reconning of our age, influenced by the tension and turmoil of our post-pandemic consciousness. Here Asquith also uses these icons as metaphors for perception, with varied patterns suggesting differing interpretations of current events and outcomes.

The infinity centre of each work infers that the epicentres are collapsing in on themselves, perhaps as a portal to another dimension or a star collapsing in on itself at the end of its life. This presented phenomenon forms a central focus of the picture plane, directing the viewer's gaze and imagination to the possibilities contained within the images.

Within the bounds of the wavering compositions, the viewer’s gaze continually returns to the eyeball at the centre of each image. Functioning as an axis, it guides the viewer to the midpoint of the image and engages them directly – always staring back. A centripetal counterpoint to the unease and disarray of the darting eyes surrounding it. The eyeballs evoke different patterns for how we respond to our environment and perceive threats of our time.

We then look to the menacing dark triangle formations that sit as guardians on either side of the collapsing infinity centre of the work. Ominous and with sharp edges, they lurk and threaten to slice the eyeballs as their patterns emerge across the picture plane. One thinks of the surrealist film Un Chien Andalou, the 1929 French surrealist film directed by Luis Buñuel and written by Buñuel and Salvador Dalí, in reference to the inferred horror and present danger these sharp-edged triangles appear to present. When Buñuel is about to slice the young woman's eyeball with a razor, she stares straight ahead as he brings the razor to her eye. The scene then cuts to an image of a cloud passing before the moon. In Asquith’s images, these menacing triangles hover and threaten to glide and sliver the eyeballs across each image at any moment.

The only variances within the repetitive compositions are the patterns of eyeballs and skyscapes that change and differ in their symbolic relationship with one another. The tropes are presented with the direction for the viewer to decipher and derive meaning from the abstract narrative. As if these works say everything and nothing simultaneously—the viewer is asked to interpret these messages and feel the response as they are present in front of the works.

Each work represents our collective physiological response to the events of our recent past—the inner world of our being. The abstract narratives portray internal responses to external incidents—lockdowns, #BLM, economic instability, destabilisation of the Asia Pacific region, the digital, our imminent environmental collapse, fossil fuels, [insert your own inescapable disaster here].

Within the convolutions of the narratives within these works, Asquith presents a dichotomy between the washed watercolour backgrounds and the sharply rendered abstractions that float above like architectural drawings for concepts yet to be fully grasped. The crisp line work contrasts the soft painterly qualities of the backgrounds, yet somehow, they are co-dependent to balance and resolve the works. Two languages and techniques are at play here, each desperate to find a voice, yet each is utterly meaningless without the other.

By Dr Aneta Trajkoski, University of Melbourne