MERRIC BRETTLE: PSYCHOPOMP 2:POETRY OF THE MECHANICS

MERRIC BRETTLE

26.11.25 - 20.12.25

Installation images

Psychopomp 2 - The Poetry of Mechanics.

At the heart of my practice is an exploration of what it means to be an individual within our contemporary socio-cultural condition. With this in mind, I make two types of work. The first investigates what this condition ‘is’, and the second expresses my reflections on what it means to ‘be’ within it.

The first type of work therefore, investigates the social world we share, as I collect and remake bits of it that convey some ‘sense’ of it to me. These ‘bits’ are all images from the Internet, and the works I make from them are my Pattern Finding pieces. In these works I reverse engineer these sense/samples and explore how they ‘work’ on me.

It is by capturing the look of screen backlighting, for instance, that I come to understand our experiential relationship to a mechanised culture, and by making abstract pieces using colour pallets from advertising material, that I get an idea of a socio-cultural mood.

In these works, ‘I’ exist in their translation from sample image to object, and the ‘marks’ of my presence relate to ‘impression’ as opposed to ‘expression’.

While constructing these works is an ongoing process, there is another type that I make paral-lel to them. These are my Reflection pieces, and they express ‘what’ I considered this condition to be, ‘the way’ that I saw it, and ‘how’ I understood being within it at different times. In them I employ an expanding number of systems of being creative, in series, to explore my ideas.

In some of these system/series, for example, I add to pattern finding pieces and overlay them with other materials to express the personal relationship I had with them when I ‘found’ them. In others I join two or more samples to explore a resonance that express’ something else. In yet others I explore the materials, methods and images I found in my pattern finding works, as a kind of language through which to express my ideas. These systems/series are represented in the Liminal Object, Ritual Process and Sense Data works shown here.

In these works ‘I’ exist in them as samples, yet also in the choices that my system/series afford. Consequently, within them, the ‘mark’ of my presence is multiple, exists in layers, and expresses both impression and expression.

Contemplating the works in this exhibition, they are all ‘visual poems’ and as such they are all emotional and experiential responses to ‘being in the world’. In saying this however, their poetry probably lies just as much in the mechanics of the systems I use as in the surface image I construct.

With this in mind, I hope that the viewer reads the works formally as they would allow for the poetry in these mechanics to be seen. Consequently, I would like them to consider the works as experiential metaphors of they way that I as one individual came to terms with our strange new digitized and globalised condition.

It is as an experiential metaphor thus, that I hope for them to explore the systems I employ to make work, as they reflect those that we all use to understand reality itself. That they consider the levels of choice that these systems generate in the works, as they create a ‘space’ between the viewer and object for them to explore. And that they understand the ‘senses’ that they receive from the work themselves, as they are a product of not just my agency, but also of the worlds on me.

Seen in this way the poetry of this ‘rude mechanical’ lies in understanding my works as personal ‘flights of being’. The mechanics of my poetry understood as the systems I devise to explore the possibilities of my own creativity. And the beauty of these mechanics, as to me, these poetics of creativity, express the limits and possibilities of ‘being’ itself.

Merric Brettle, 2025

ARTWORKS:

david freney-mills: continuum

DAVID FRENEY-MILLS

01.10.25 - 25.10.25

Installation images

Continuum

David Freney-Mills approaches abstraction as something alive, shifting and adapting like an organism. His paintings hold the traces of thought, cuts, layers, and gestures that build into constellations of presence. Language becomes his subject, not written or spoken, but sensed as an evolving system of signs, shapes, and rhythms.

In his first solo exhibition at Blockprojects, titled Continuum, Freney-Mills presents painting as a dynamic encounter rather than a static object. Central to the exhibition is the Hyperglyph series. These artworks start with ink applied to Korean hanji paper, which is then hand-painted, torn, and rearranged before being mounted on canvas. They convey a sense of movement and transformation. The overlapping and dissolving fragments resemble glyphs from a lost script, creating an atmospheric presence that evokes memory and the continuity of thought across time.

Freney-Mills moves easily between traditions. His work embodies the discipline of reductive abstraction while also drawing inspiration from East Asian aesthetics, including ink painting, calligraphy, textile dyeing, and woodblock printing. This dialogue produces paintings that are direct, sensorial, and quietly transformative.

The works carry the resonance of history while speaking in a voice that feels entirely of the present. They invite an experience that is both immediate and enduring, a language of presence and transformation that unfolds differently for each viewer.

ARTWORKS:

jarryd Cooper: juggernaut

Jarryd Cooper

Jarryd Cooper

03.09.25 - 27.09.25

Artworks

Jagganath

Philip Guston put down his brush and crushed his cigarette out in his palette. Ash pink dawn was breaking, and the cold light crept into his studio and cast an illuminating ray over his efforts, confirming what he had started to suspect. Completion.

What was it he saw there, in the countless strokes and scrapings? Some great steamroller. A chariot of dread proportion ploughing its way through all before it. From beneath the weight of the heavy roller, prickly legs issue forth in agony, crushed crimson and bulbous. Their shoes, horse shod, turned upwards to a bloodshot sun. He had always preferred Newton to Einstein. The gravity of it all!

He had been at it all night. He ate spaghetti and meatballs with Musa then made the short walk to the studio. When he squeezed out his first pustules of cadmium red, everybody was there. Friends, family, peers, critics. The whole bloody pantheon. But as he pondered and paced, and prodded and prised, one by one they all started to leave. Just like he always said they would. Was he going to leave too?

He took out his iphone and opened the camera. The clack of the shutter. A pale facsimile. Crooked and bowed, a deformed likeness if any. His thick and clumsy digits, so deft with the brush, plodded and fumbled numbly across the sleek paint smeared device, and eventually stumbled into Instagram.

He had never even wanted it. Bill de Kooning had persuaded him to get it. He had been late to Facebook too but had gradually succumbed. His last post read something along the lines of… “I do not give Facebook or any entities associated with Facebook permission to use my pictures.”

All his poet friends were on twitter, and he secretly wished he could join them. But Bill could be so persuasive. It’s freedom Phil! And that’s your true subject!

Ah well. Give it a go! What’s the worst that could happen?

*

The sun is starting to rise up over the trees. Crows perch on power lines and a cat knocks over a dustbin. But Philip can only stare in anxious wait at the greasy portend. Nothing. Why is it taking so long? Idiot. You fool, you should never have been so stupid. How could you let Bill talk you into this? To think that anyone could possibly appreciate what you’re doing. And what’s happened to you? In what sad pathetic world would anyone with a shred of integrity resort to… wait. A flash. A buzz. Like flies waking, and picking up their first scent, steadily they start to swarm. The dam busts open, and the deluge of approval washes in like a flood. He can’t fathom it. The adulation, the glory, all there in his paw.

No jibes and snide remarks. No accusations or mention of mandarins and stumblebums. Just positivity. Yes. Just nice words of affirmation. They like it. They actually like it. I’ve made something that people like. Fuck!

Thumbs up. OMG love this! The Pink is on point!

What do they mean by that, on point?

Now what, they’re making comparisons? Oh Jesus!

Love the Krazy Kat vibes. You should check out George Herriman. Hey @robertcrumbofficial get a load of this! Fuck yeah dude channelling some hungover De Chirico energy.

Oh, God stop! Stop! He tries to write back to these people. Tell them they’re wrong. Tell them the painting is a failure. An utter failure. But Bill didn’t teach him how to respond. Didn’t show him where it’s @

So, he shouts into the void. Can’t you all see this fraudulence? Can you not see you’ve been hoodwinked?

What have I done? They had all gone. They had finally left me alone, and then fool that I am, frail creature of vanity, I invited them all back in. I opened the box. I threw myself under the rampaging wheels of Jagganath. I am solely to blame. This and many more desperate utterances are spat into the chasm, unaware that with indifference, the algorithm had ploughed on, swallowing his words like a street sweeper, churning them up, perhaps to one day cast them adrift, to wash up on a desolate foreign shore.

Haggard and bereft, his day ruined, he lights a cigarette and takes a deep contemplative drag. Nothing to do now but paint. He takes his titanium white and empties it onto his palette. With his biggest brush, he begins to erase and undo. But he struggles against the weight of that mighty chariot. All that red and black, still wet, still living. History is written by victors and Guston wasn’t winning. But gradually things settle, and he relaxes into the process. Slowly though, he starts to sense something. A sound. What is that? Some kind of tone. Tinnitus? No, far worse. A high pitch note, constant, without break. It’s near. It’s inside the building. He steps out of his studio into the hallway, and follows the sound to a room he never even knew was there. No Entry. DANGER. Cellular site. TELSTRA. What is Telstra doing in Upstate New York? Subsidising his studio? Paying his rent? Funding his entire existence? Have they been listening this whole time? Would you believe it? The door isn’t locked.

Inside, everyone is there. Bill, Morty, even Jackson. John is performing four minutes and thirty-three seconds of silence. In this version, two split systems rage against the heat of a giant computer running hot, and that same ear-piercing tone, strikes its blistering knell. Lights flash green, but one is red, bloodshot even, and it doesn’t flash. It sits static, radiating like it were painted. It hums along to the silence. A socket beneath it plays host to a snaking cord. He’s down to one line now. With Mickey Mouse gloves, he grips it. The line goes taut and Guston, sweating under his hood, tastes salt on his lips. Well, he says to himself. What’s the worst that could happen?

Written by Harry Hay.

Hay is a painter and writer based in Melbourne.

ARTWORKS:

darren munce: snakes & ladders

Darren Munce

06.08.25 - 30.08.25

Installation Images

SNAKES & LADDERS

Dear Darren,

You told me over the phone you felt to always be saying the same thing about paintings. I know the feeling, but once the call ended I got thinking about why that might be such a bad thing. Or what the compulsion even to say new things is or where it comes from or why it might be least useful, especially, and most of all, when dealing with something as mysterious and obvious as a painting.

Have you ever seen the Paul Klee painting The Snake on the Ladder? I love the title more than the work. If the snake is on the ladder we can neither climb upward nor slide down. Which is a way of saying that action organises grammar or grammar organises action. Either way, the snake and the ladder entwine and our reading of both must change.

I’m writing this from a plane and the coastal low has scalloped the air up here. We shoogle like gravel in a gold pan. Crazed waves break in all directions below us, sea looks roughed with sandpaper. The sun hits the wing and I’m blinded. I wish I understood the weather like I wish I understood engines. It exists to me mostly as a vague, unruly and persistent claim the world makes unto itself, a kind of petulance we accommodate with a set of instruments that tell us where not to be and when. Flight routes are altered, towns evacuated with warning or with sudden fire or water.

But this isn’t a climate letter. Though perhaps it is a things turning up in ways we don’t expect letter. Like a snake on a ladder. Or the scuzzy flecks of an underpainting skulking below the final layer.

Which I was reminded of recently when a doctor scooped a benign lump from my forearm. I watched him insert and tighten stitches, arrange narrow tabs over the wound, dab it with minerals, align and smooth a dressing over the lot and finally waterproof it with a strange sticky plastic. At which point the whole configuration seemed to shimmer and I felt to be seeing through the gauze itself and looking upon the tabs and minerals and stitches which had been covered only a moment ago, and then through them into the cavity which they were put there to seal, and then through even that, through time, through every other surgery my doctor has ever conducted, through his medical training, through each and every overdetermined current buoying him into his profession and me atop his operating table. I thought of you, of our friends, bent over their various labours––paintings and poems and songs––delicately applying, shifting and removing things in an unruly and persistent submission to claims the world makes unto itself.

Which is to say, Darren, the weather is the weather. How we proceed––in those labours or in travel––is a matter of how we read it. Let’s see if the snakes uncoil.

Love,

Gabriel

Text by Gabriel Curtin

ARTWORKS:

Stephen eastaugh: fluffy geography

Stephen Eastaugh

14.05.25 - 07.06.25

FLUFFY GEOGRAPHY

In Fluffy Geography, Australian artist Stephen Eastaugh offers a tactile, poetic meditation on movement, place, and the fluid geographies shaped by memory and imagination. Developed across Taiwan, Fiji, and Australia, the exhibition brings together 37 small-scale works that blur the boundaries between map and memory, language and landscape. Made from salvaged wood, thread, fabric, and gouged text, each piece functions like a signpost—yet rather than pointing toward fixed destinations, these works invite drift, reflection, and intuitive navigation.

For more than four decades, Eastaugh has embedded travel into the core of his practice. Having worked in over 80 countries—including multiple long residencies in Antarctica—he creates from the perspective of the perennial outsider, one who engages place not as a backdrop, but as a collaborator. Yet Fluffy Geography is not about documenting travel. These are not souvenirs. Instead, they are markers of inner topographies—visual and linguistic fragments shaped by movement and material.

Each work resembles a directional sign, but what it directs is uncertain. Abstracted panoramas sit alongside single-word inscriptions gouged into the wood—symbols and scenes that hover between clarity and suggestion. The stitched elements and worn surfaces hint at landscapes that may be remembered, imagined, or entirely invented. The use of text does not explain but deepens the mystery. Words here feel like found thoughts, partially buried or weathered over time, inviting interpretation rather than instruction.

The title, “Fluffy Geography,” encapsulates the conceptual tension at the heart of the show. “Fluffy” evokes softness, atmosphere, and a sense of ambiguity. “Geography,” by contrast, implies order, measurement, and control. Eastaugh brings these opposing forces into conversation, allowing them to coexist in each piece. What results is a kind of emotional cartography—artworks that don’t chart space so much as they suggest how it might feel to move through it.

Rather than offering a linear narrative, Fluffy Geography unfolds as a dispersed landscape of thought. Each work is a waypoint, not in the navigational sense, but as a moment of pause—an invitation to stop, consider, and reorient. These are artworks made to be read slowly, felt physically, and understood over time.

Stephen Eastaugh’s ongoing commitment to working with found materials—wood scarred with age, fabric frayed by use, thread as both line and suture—adds to the sense of lived history embedded in the work. In his hands, the act of stitching becomes an act of mapping; the gouging of words, a form of excavation. Together, these gestures form a language that resists certainty and celebrates ambiguity.

Fluffy Geography offers no destination and no clear route. Instead, it proposes a different kind of journey—one shaped by intuition, memory, and openness to the unknown. Eastaugh reminds us that place is never just where we stand, but how we feel, remember, and imagine. In this world of soft signs and shifting symbols, the viewer is invited not to arrive, but simply to wander.

Q&A

BP: What conditions or contexts gave rise to the Beautiful Borders series?

SE: This series was developed during my second residency in Taipei, at the Treasure Hill Artist Village—a compact, characterful space nestled within a layered urban ecosystem. I spent six intensive weeks there: exhibiting, walking mountain trails, reflecting on Taiwan’s precarious geopolitical position, and engaging with the local art community. The looming, unresolved threat from mainland China lingered in the background, sharpening my awareness of visible and invisible divisions. From that atmosphere emerged this suite of 16 mixed-media works.

BP: How does materiality function in this body of work?

SE: Each work—20 by 35 centimetres—combines acrylic, cotton thread, fake grass, metallic paint, watercolour, felt, and Belgian linen. I deliberately chose a tactile, sometimes contradictory palette. Softness alongside synthetic, stitched lines crossing open fields. These materials behave like borders themselves: shifting between containment and permeability, comfort and friction.

BP: Borders are central to the series—what draws you to them, conceptually?

SE: Borders occupy a liminal terrain that is both real and symbolic. I’m drawn to their contradictions—how they can simultaneously separate and connect. They operate like emotional seismographs: sites of joy and sorrow, confrontation and reconciliation. I see them as see-saws—tipping between states, never still. They’re where abstraction and representation meet, where politics collides with personal experience.

BP: How do you articulate the shifting nature of frontiers through your imagery?

SE: I stitched barbed, red thread and scattered grid-like formations across ambiguous islands—gestures that suggest mapping, but resist legibility. These visual interventions aren’t literal—they’re speculative. They mirror the unstable, often contradictory character of borders: places where strangers encounter one another, for better or worse. The ambiguity is intentional.

BP: Do you imagine a future for borders beyond their current function?

SE: That’s the hope buried in the title. Borders can be violent, bureaucratic, cold—but they can also transform. Frontiers become walls, then trenches, then maybe bridges. Landscape, of course, doesn’t care about our divisions. The idea of beautiful borders isn’t naïve optimism—it’s a provocation. A hope that these charged zones can evolve into places of genuine, humane encounter.

REQUEST MORE INFORMATION ABOUT THE EXHIBITION ENQUIRE

ARTWORKS:

enquire.

david walLage: free falling

David Wallge

09.04.25 - 10.05.25

David Wallage: Free failing

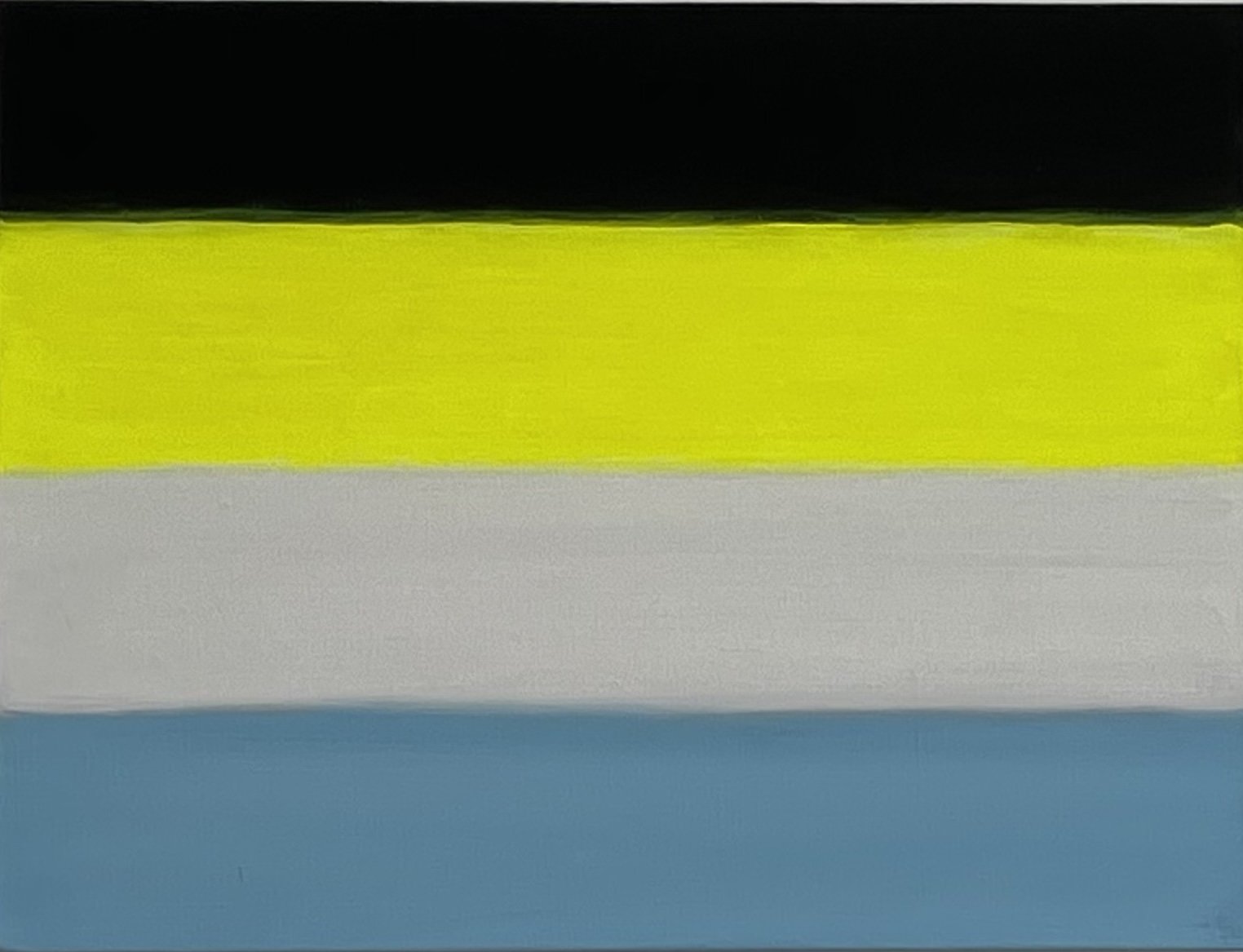

David Wallage's latest exhibition, Free Falling, explores the essential elements of painting and sculpture. Wallage approaches his work with a commitment to abstraction, seeking to understand the most essential components of art—form, colour, and material. His approach echoes the modernist tradition of non-representational art, influenced by ground-breaking figures such as Joseph Albers, Imi Knoebel and Agnes Martin.

Wallage's process is driven by a desire to eliminate excess, distilling his work to its most basic and essential aspects. Albers famously stated, “Simultaneous contrast is not just a curious optical phenomenon—it is the very heart of the painting,” emphasising the critical role of colour relationships. For Wallage, this idea serves as a foundation for his creative process, where the interaction of colours and materials is central to the artwork's meaning and impact.

For Wallage, each painting becomes an opportunity for experimentation, working serially and continuously refining his exploration of essential forms. His use of materials remains straightforward, focusing on the tactile relationship between the surface and the viewer. Wallage remains committed to a rigorous, abstract practice that does not simply create art but instead attempts to unearth the fundamental relationships that define our interaction with the visual world.

ARTWORKS:

enquire.

JAMES CLAYDEN: 100 DRAWINGS 2020 - 2022

James Clayden

12.03.25 - 05.04.25

James Clayden: 100 Drawings

"These drawings were made between 2020 and 2022 when for no reason l kept them roughly the same size. They weren’t done with paintings in mind, but purely as intimate drawings for themselves alone. When l looked back over them l thought they could possibly go together in a small landscape format book. I had them photographed and slowly l began arranging them into the order they are in this book. There seemed to be a good feeling to the idea of there being 100 drawings, so l made a selection from all l had done in that time and here they are."

James Clayden, a visionary painter, filmmaker, and musician, presents 100 Drawings 2020-2022, a collection that offers an intimate, raw exploration of his creative process during the global pandemic. Through these drawings, Clayden distils his ongoing fascination with abstraction, form, and the delicate interplay of space—unveiling a personal and visceral narrative of artistic evolution.

Spanning two years, 100 Drawings captures a moment of transformation, allowing us to witness the artist’s journey as it unfolds across each piece. This exhibition reveals not only the development of Clayden’s distinctive language but also his deep engagement with the rhythms of time, space, and perception.

Accompanying the exhibition, Blockprojects is proud to release a comprehensive publication showcasing the full series of 100 drawings, offering a deeper insight into Clayden's world and the evolution of his art during these pivotal years.

ARTWORKS:

enquire.

marc freeman: all things being equal

Marc Freeman

12.02.25 - 08.03.25

Marc Freeman: All things being equal

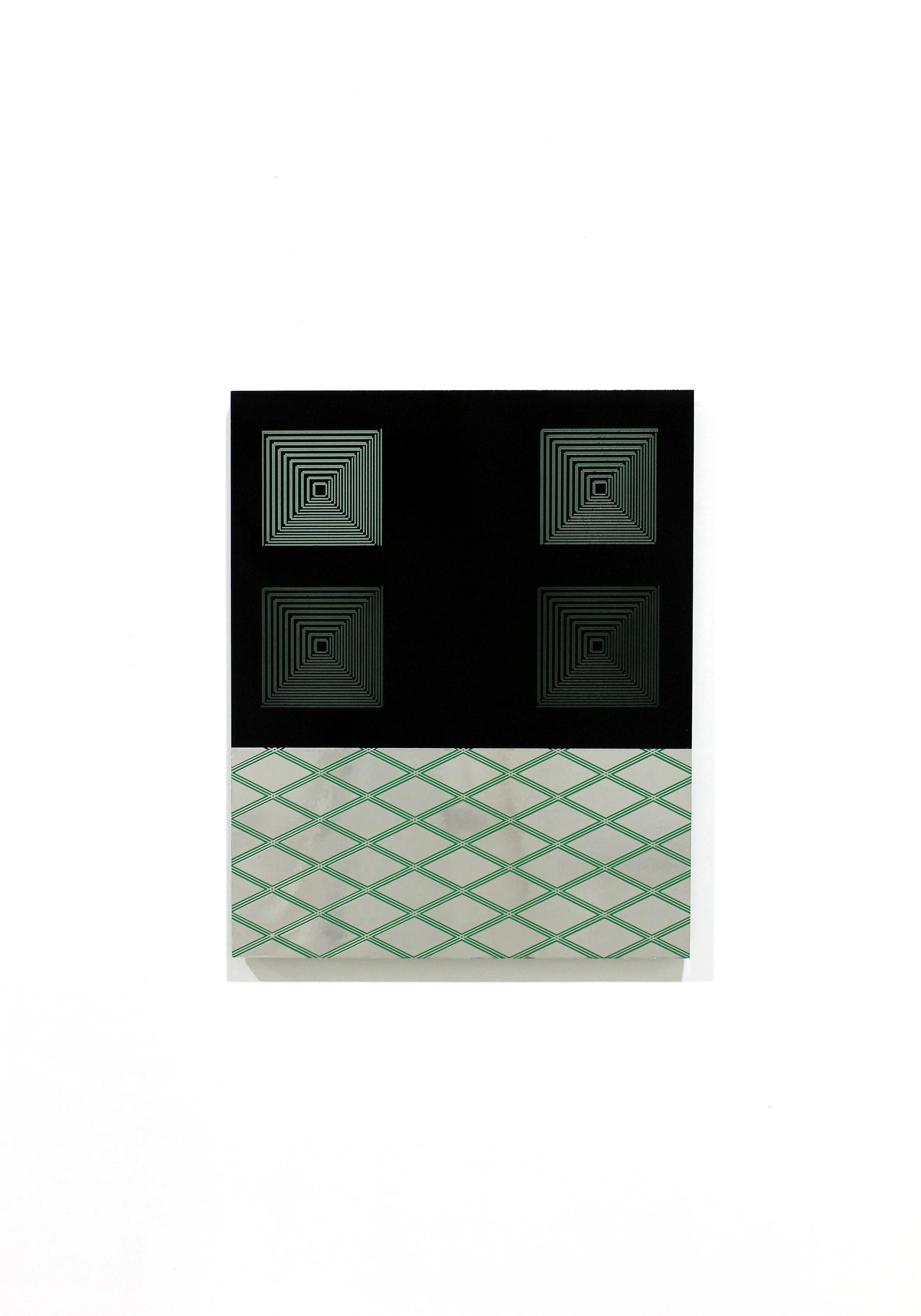

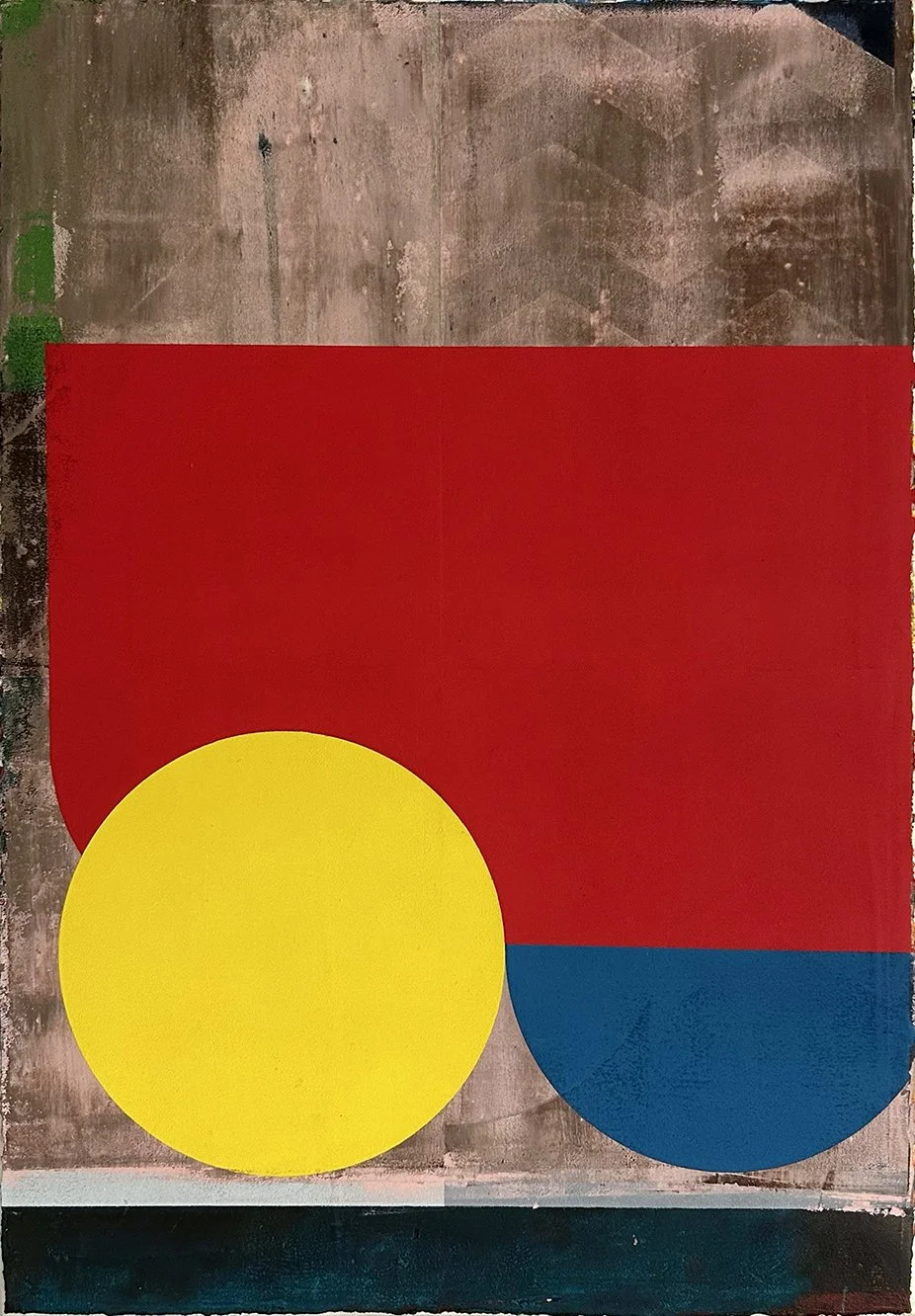

In an age when the digital and the physical intermingle with increasing ease, Marc Freeman’s latest exhibition, All Things Being Equal, examines the delicate dance between historical iconography and contemporary visual culture. The show dissolves rigid artistic boundaries, offering a space where classical painterly traditions and the aesthetics of algorithmic design meet, forging a landscape in which past and present exist in constant dialogue.

Freeman’s latest body of work treats painting as both an act of excavation and reinvention. He retrieves, dissects, and reconstructs historical references through a distinctly contemporary lens. These compositions shift seamlessly between the digital and the handmade, challenging established hierarchies and collapsing the divide between medium and time. Elements of pixelation, glitch aesthetics, and machine-generated forms intertwine with expressive brushstrokes and careful composition, blurring the line between fleeting digital imagery and the permanence of paint on canvas.

A key reference point here is Frank Stella’s late-career embrace of digital technologies—his evolution from strict minimalism to computationally generated three-dimensional structures serving as an important precedent. Freeman follows a similar trajectory, disrupting linear art-historical narratives by merging abstraction and tradition. His inclusion in Thames & Hudson’s 100 Painters of Tomorrow, as well as his exhibitions in New York and Beijing, position him within a contemporary conversation on materiality and technological mediation. His receipt of the Marten Bequest Traveling Scholarship speaks to the expansiveness of his practice, both in terms of geography and conceptual ambition.

All Things Being Equal resists the temptation to frame tradition and innovation as opposing forces. Instead, it proposes a continuum—one where artistic methodologies evolve and hybridise. In Freeman’s work, painting is neither a nostalgic return nor a futuristic leap; it is an ongoing negotiation with time itself, investigating how images endure, adapt, and assert their presence in an ever-shifting visual world.

ARTWORKS:

enquire.

peter graham: diviner

Peter Graham

20.11.24 - 20.12.24

peter Graham : Diviner

‘Diviner’ is a project comprised of figurative studies, that depict an artist as a kind of primal, magical entity inhabiting a workshop within the mind. Sometimes long hours are spent in the studio staring dumbly at blank surfaces so that eventually a lack of inspiration becomes subject for the work itself.

At these times I have made observations of my own artistic practice as if it were some (absurd) ritual, undertaken in order to transcend its own limitations. I have often depicted my surrounding workshop like the interior of a giant head-space, a vault with indication of openings into the external world that exists beyond.

The figurative forms operating in this underworld are like bodily manifestations of an artist’s imaginative intent. I wonder how consciousness might extend its reach beyond the internal regions of a body, as if our physical-self was a slave to the spirit that motivates its actions. That an exhausted artist is like a golem to their inner creative drive: we are thaumaturgic beings, spellbound to motivate beyond the despondency and despair of an imagination in decay.

The paintbrush is like a wand, or antennae- a dark spark, or spore; as well as a hairy stick that seems to stop short of everything. I imagine a type of magical activity beyond its sad failed reach as if it were a lamp illuminating interior spaces on the other side of a picture plane. There the artist ventures like an archaeologist, attempting to steal the shine reflecting off a deeply kept secret located in the bunker of the mind.

ARTWORKS:

enquire.

jo wilson: wood/line/pins

Jo Wilson

16.10.24 - 16.11.24

Jo Wilson: wood/line/pins

While nature and industry are not immediately obvious counterparts, they are the primary and consistent themes that characterise Jo Wilson’s recent art practice. Her work is distinctive both in its use of natural materials – typically reclaimed timber which is selected for the beauty of its grain, texture and colour, as well as its history – and in terms of the ongoing and wide-ranging influence of the plastic injection moulding factory that was established and operated by her father. Wilson’s studio is based at the factory and the varied elements of this familiar industrial setting provide a rich repertoire of source material that has inspired her work over many years. While others may not see beauty here, for Wilson, who is acutely aware of her environment and sensitive to its details, it is a site of artistic potential and constant creative renewal.

The woodLINE totems in this exhibition are based on steel tooling components stacked in imaginary assemblages which have been turned on a lathe into a series of single towering forms. Shape and line are perfectly calibrated in these works, but the precision of their design is interrupted by the natural features of the cypress – the irregular patterns of its grain, variations in colour and random knots in the timber – establishing a compelling interplay between the manmade and the organic. The same dynamic operates in the Channels and Pin/Point series where details from the factory are replicated in metallic paint and playfully coloured miniature pins (also turned on a lathe) on panels of richly figured cypress and oregon. The silver painted sections in these works follow the linear format of channels in plastic palettes which Wilson has sketched and photographed in the factory and while they recall the sheen of industrial machinery, sometimes appearing solid and dense, in certain lights the paint is also translucent, deliberately chosen so that the grain of the timber remains visible.

Wilson feels a strong connection with her medium – she loves its tactile material qualities, its patterning and tonal variation, even its scent. She is excited by the prospect of transforming discarded raw material into something beautiful and giving it new life. Beyond this, she is also conscious of the timber she uses as having an energy that connects it directly to the natural world. She observes the finely-set grain lines of one panel which indicate years of growth, for example, with fascinated awe. The slow, often hand-worked and labour intensive nature of the techniques that Wilson uses allows her to focus on these qualities, showing respect for the medium at the same time as stilling her own thoughts in a therapeutic form of making as meditation.

KIRSTY GRANT

Kirsty Grant is a curator and writer specialising in Australian art. She previously served as the Director of Heide Museum of Modern Art and was the Senior Curator of Australian Art at the National Gallery of Victoria (NGV).

ARTWORKS:

enquire.

julia powles: all these galaxies inside us

JULIA POWLES

18.09.24 - 12.10.24

Julia Powles: all these galaxies inside us

In her most recent solo exhibition Julia Powles maps out a trajectory of human feeling. A large series of black and white drawings titled A brief history of crying, runs along one wall of the gallery. In this work we find numerous tear shapes - a common motif for Powles - drawn in white pencil and chalk onto ink; erased and re-drawn in a manner reminiscent of a blackboard, the site where lessons are learned. With so many tears washing down the wall, we are reminded that weeping is also a collective action, and that through compassion and empathy we can find unity. Made using her engineer father’s drafting equipment – compasses, rulers and French curves – Powles employed tools that were once used to design the built environment, as a means for expressing inner emotions.

Similarly, a Venn diagram of overlapping circles has been painted onto a blanket that belonged to the artist’s mother. The schematic blanket painting operates as a kind of family portrait with members overlapping in significance, casting shadows and creating absences. So much happens, Powles says, in bed: sex, love, birth, death, illness, crying and dreaming, while the blankets, kept for years in her mother’s linen closest, bear witness to those events. In reusing her mother and father’s possessions to make art she can not only redeploy functional materials but embed the lived experience of others into her working methodology.

The paintings and drawings in this exhibition span a four-year period during which Powles sought to represent ideas relating to time and experiences. Sound waves, thoughts that resurface, stories told and retold, memories (actual and repressed) are manifest in paint through echoes, reverberations and ghosts – lines and colours repeat in more and more corrupted manners, shapes are erased, one form is buried beneath another, spatial structures emerge and collapse. A small relief sculpture completes the exhibition, appearing as a series of loops it is in fact a sentence: All these galaxies inside us. Made from a single coil of clay and gilded with silver leaf, the barely legible nature of the text is, like so much of our confusing, complex emotional lexicon, obvious once we can see it.

ARTWORKS:

enquire.

vivian cooper smith: patterns of the eclipse

VIVIAN COOPER SMITH

14.08.24 - 15.09.24

vivian cooper smith: patterns of the eclipse

In his new exhibition ‘Patterns of the eclipse’ Vivian Cooper Smith draws inspiration from minimalism, science fiction, and new age aesthetics to challenge photography’s conventional boundaries. His work invites viewers to discover meaning not just in the subject matter, but in the haptic process of creation itself.

Central to Smith’s work is the model of an eclipse—a cosmic alignment that both obscures and reveals, casting shadows on Earth and creating spectacles for its inhabitants. Smith recreates this phenomenon within his studio, positioning the camera as the situated earthbound observer. Before the lens, an arrangement of geometric objects and paper cutouts intersect and obstruct one another in a fluid, ever-shifting composition. Light passes through this scene and encounters a diffraction grating on the camera lens where it proceeds to unravel and reform into an array of patterns and colors.

This studio-based methodology embodies ideas derived from the writing of Karen Barad, who proposes (among other things) that new ideas emerge not from opposing differences, but by working through and with them. Smith’s approach thus becomes a visual manifestation of Barad’s philosophy. Each object in his studio setup exists not in isolation but in relation to others. The resulting photographs stand as visual testaments to this worldview, where obstruction and intersection don’t hinder creation but become essential to it.

In essence, Smith’s work is a meditation on the generative power of difference and obstruction. It challenges us to see beyond binary oppositions and instead explore the rich patterns and insights that emerge when we allow diverse elements to interact with and inform one another.

Artist statement:

This exhibition has been one of the most challenging to create for various reasons. Time for studio experimentation has been limited, and my creativity has been challenged by a mind and body committed to and distracted by competing priorities. There have been many times when I have felt eclipsed. However, while it may be a disservice to Karen Barad’s work to suggest this, it remains no less true that obstruction and disruption can indeed create space for surprises and joyful outcomes. These photographs are the result of working with and through the challenges my art practice has faced in recent years.

ARTWORKS:

enquire.

David Thomas: the passing of days and nights

DAVID THOMAS

09.07.24 - 10.08.24

david thomas: the passing of days and nights

Simply put the exhibition is diverse/complex and requires slow viewing. I see it as a journey through various aspects of life, celebrating the intimate and the grand.

THE PASSING OF DAYS AND NIGHTS has a contemplative function.

THE PASSING OF DAYS AND NIGHTS is a COMPOSITE exhibition of abstract paintings, photopaintings, titles, photography, and structures.

THE PASSING OF DAYS AND NIGHTS presents new works that explore the perception of time, space, complexity, impermanence, memory, and feeling.

My PAINTINGS are mainly from the ongoing “Gently Painted Series”.

They are complex in a simple sort of way. They manifest the factual reality of the painting’s materiality, temporality and form. Colour evokes a sense of boundless time/space/ energy. They reveal the sensibility /sensation of human touch in time via surface/facture and celebrate the INTERIOR non-material world of feeling/spirit / thought.

My PHOTOGRAPHY reveals its own material realities (physical, digital, mechanistic). It records the specific, the details of the EXTERNAL everyday world. it activates memory, sentiment, at times reflecting the absurd, the sometimes beautiful, and the sometimes bitter-sweet world of PAST EVENTS.

My use of TITLES is POETIC creating entry points into the work. The titles can be literal, conceptual, humorous, ironic, paradoxical, deeply felt. They act as triggers for recovering content.

The JUXTAPOSITION of the various elements/durations in the exhibition creates COMPOSITE RELATIONSHIPS (at times surprising) between language, form, media, and content… at times simple, at times complex like the world itself.

David Thomas

David Thomas Biography:

David Thomas was born in Belfast N. Ireland. He studied at Melbourne, Monash, and RMIT Universities. He lives and works in Melbourne/Naarm, Australia. His work explores the contemplative function painting, photopainting, and installation, in particular, how new iterations of the monochrome tradition and the composite can explore the perception of time, space, complexity and impermanence. He holds a PhD from RMIT University where he is an Emeritus Professor in the School of Art. He occasionally curates and writes on contemporary Eastern and Western art.

His work is held in numerous private and public collections in Australia and overseas including: National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne. Australia. Australian National Gallery, Canberra, Australia. Heide Museum of Modern Art. Melbourne, Australia. RMIT University, Melbourne. Australia. Cripp’s Collection, Australia and UK., Gippsland Art Gallery, Victoria, Australia. Ballarat Art Gallery Victoria, Australia. Chartwell Collection, NZ Auckland Art Gallery, New Zealand/Aotearoa. Lowenstein Collection, Melbourne, Australia. Canterbury University, Christchurch, NZ /Aotearoa. Lim Lip Museum, Gong Ju, South Korea.Theodor F. Leifeld Stiftung, Kunstmuseum Ahlen, Germany. Kunstmuseum Bonn, Germany, The Frederick Collection, Germany, Justin Art House Museum, Melbourne.

He is represented by: Block Projects Melbourne, Australia, Minus Space, New York, USA and raum 2810, Bonn, Germany.

ARTWORKS:

enquire.

robert doble: the glasshouse

ROBERT DOBLE

26.06.24 - 06.07.24

ROBERT DOBLE: THE GLASSHOUSE

ARTWORKS:

enquire.

peter westwood: the new way to live

PETER WESTWOOD

14.05.24 - 08.06.24

Peter Westwood: The new way to live

Peter Westwood is an artist, curator, arts writer and academic. His work is focused on ideas of unsettled and uncertain times. Peter has worked in various media however his practice is primarily formed through a long-standing preoccupation and interest in painting.

In the title of Peter Westwood’s latest exhibition, we find a clue. The new way to live suggests that an alteration or schism in the way we approach the world has occurred. The old ways have receded, a fresh way to live is required, but how do we recognise it? How do we grasp its form? In an era of uncertainty – a heating planet, wars, economic displacement, rising global intolerances – in a world, we increasingly experience as fleeting and fragmentary, Westwood proposes a survival strategy of radical momentariness, where each fragment, each encounter can be experienced as a totalising instance. Something inexplicable glistens on a flat blue background, two miniature arched rainbows hover in tandem, a nighttime garden has plants with branches and roots that cross over each other with lines sharp as knives, abstract patterns tumble down from ceilings, and shapes we feel we should be able to recognise recede into multi-coloured backgrounds.

The new way to live puts forward the idea that to be in the contemporary world is to experience life as an accumulation of fragmentary moments, both ubiquitous and peculiar. Rather than seeking a structure within this tumult we could, Westwood’s painting suggests, accept the chaotic moments as a sequence of equivalences where what matters is not a rationale, but an immersion.

Westwood has been included in group and individual exhibitions in public and commercial galleries in Australia and overseas. He has also curated exhibition projects for the past 30 years in Australia, and periodically overseas, and is represented by Blockprojects Gallery in Narrm/Melbourne, Australia, and Boutwell Schabrowsky Gallery in Munich, Germany.

in conversation: Peter Westwood & BLockprojects

Tell us about yourself.

I was born in Sydney (on the lands of the Gadigal people) eventually moving to country Victoria (to the lands of the Wadawurrung people), and finally then to Melbourne/Narrm in the early 1980s to study at the School of Art at RMIT University.

From a very young age, I had thought that I would become an artist as I was captivated by drawing and painting. This was partly due to having had an artist in my family, an uncle who was relatively successful during the 1960s and 70s. But my childhood in the country was also marked by instability, and I guess that this was another reason that I became an artist. As a child, drawing and painting seemed to be a way of making sense of a confusing adult world and an unpredictable household. Creativity not only formed a space of solitude and interiority for me, but in retreating to my bedroom to draw, I was able to make sense of, and intuitively express feelings about the world I lived in.

Making art has remained a primary way for me of understanding and clarifying the eccentricities of our human condition. In the main, my artworks are formed entirely through experiences where I channel my feelings and thoughts around what I consider to be a complex and ambiguous, but deeply engaging world.

I have taught in various art schools, and in my teaching, my principal method has been to encourage students to make contact with their feelings and to employ conscious and unconscious workings as a primary method of creative production. Of course, a capacity for skills, analysis, understanding, and knowledge are also primary factors for young artists to develop.

But what I discovered early in my life is that the thing about painting is that it has the capacity to bring ‘the world’ into an intimate space. In painting ‘the world’ artists can represent life as a sensual experience, freed from the manoeuvrings of our day-to-day interpretations and understanding.

I’ve also encouraged our three children, by some means, to trust their intuition because sometimes we feel things within our bodies before we are even aware of what it is that we are thinking. In working with these art forms I’m often surprised by my bodily response to colour and the materiality of a medium, even prior to ideas eventually revealing themselves, unfolding as thoughts about ‘the world’.

What process/method are you exploring /experimenting with at the moment?

No matter what the medium (painting, printmaking, drawing, video), I approach every new work as a unique experience, and in essence, I discover the content of a work by making it.

My processes and methods have always involved working from a random photograph that I’ve taken, towards a painting, print or drawing. The final artworks bear very little resemblance to the original source material.

Having finished a series of large- and small-scale paintings, I am currently working on a series of 7 screen prints (each as an edition of 6, and an artist proof). The prints range from three to eight colours, forming imageries that capture something of the atmosphere of our current times.

The prints will be presented initially at Blockprojects before being sent to Munich, Germany. In Munich, they will form part of a two-person exhibition with Julia Powles in June 2024. The exhibition is titled ‘What we feel and what we know’ and the work will be shown at Verein für Original-Radierung. The prints will also be exhibited with drawings at Boutwell Schabrowsky Gallery in Munich.

How do these processes/methods inspire your themes, concepts & ideas?

Returning to screen-printing after many years has been an enjoyable reacquaintance. Screen printing was invented around 1900 for the advertising industry, and in the mid to late 20C, it was adopted by many British and American Pop artists.

Therefore, as a medium, it leans naturally into more graphic imagery, and it’s this aspect that has been fun to work with. As my work builds via an interpretation of a photograph (a snapshot) it feels curious for me to work with a type of visual artefact that comes from the world (the photograph) while reworking the image as an unconscious response to my associations and feelings about the image. Its highly graphic, but the result is very intuitive.

In making screen prints, I’ve felt that this notion of devising imageries that evoke something that we know or feel that we recognise but also don’t really know comes very much to the forefront.

ARTWORKS:

enquire.

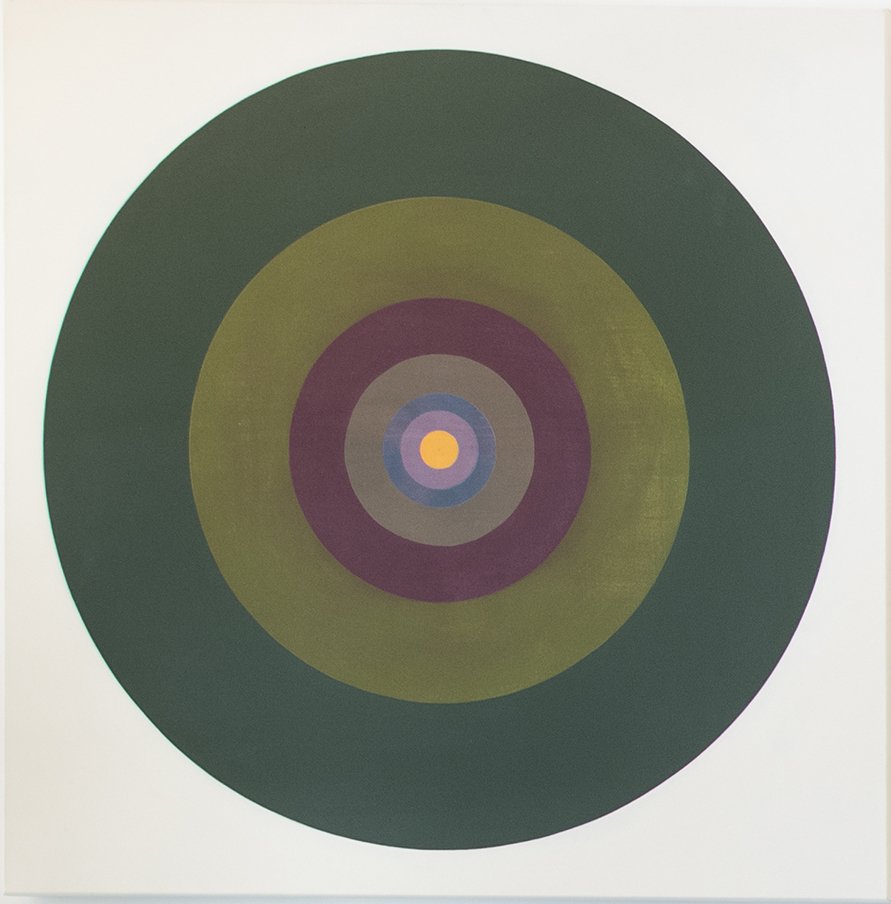

paul newcombe: opus

PAUL NEWCOMBE

09.04.24 - 11.05.24

paul newcombe: opus

The Melbourne painter Paul Newcombe has conceived a new exhibition for Block Projects in Hawthorn. Newcombe’s Opus is a group of paintings centred on visuality and a sensuous grasp of colour. It is not colour that screams brightness or speaks its surface but is the experience of something seen and fashioned into linear form.

This large opus of paintings is presented as a complete work. The paintings are all square and are in four sizes. Newcombe likes a system, and the circle and the square are his mantra and the necessary means of production. System painting suggests repetition but what is evident in Newcombe’s painting is a willingness to admit the like-for-like form of his paintings in favour of differences that are to be found in colour.

There is an analogy here which has a voice in this series. A single colour can have the like-value of an individual. Individuals are both singular and part of a group. It is what the artist Josef Albers described as ‘independence and interdependence,’ a polarity that speaks of relationships – in harmony or discord - that arise when individuals or colours are grouped together.

What further unifies the paintings of Opus are the colour bands of the compositions. They are multitudinous in hue: green – Phthalo and moss, pale blue to lighter grey, and into red, brick and brown. The certainty is here, and with it, the controlled application of synthetic polymer paint. On balance, Newcombe’s palette does not appear particularly Australian nor is it the colour of post-war American abstraction, but looks English, and would suggest painters of the 50s such as Terry Frost and Adrian Heath.

Abstract painting is tasked with remaining visible in a world that is ever more complex. We may think abstractly but we see things in figurative terms. The challenge for a painter such as Paul Newcombe and this series of paintings is to convert the moving world into abstract form. But more critically, it is the allusion, the keeping alive of lived experience, that the paintings of Opus so successfully sustain.

Brett Ballard

ARTWORKS:

enquire.

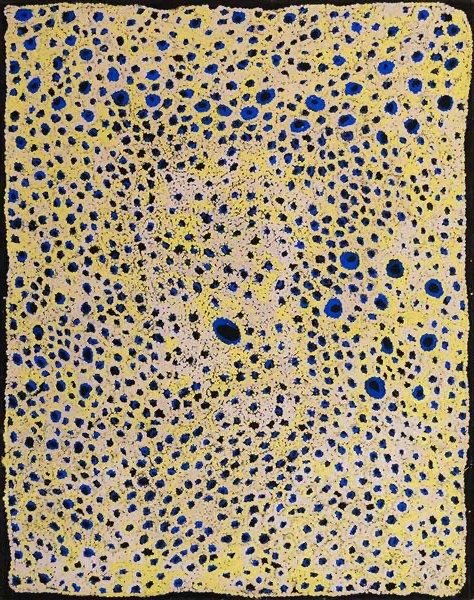

dorcas tinamayi bennett: mother’s story

Dorcas Tinamayi Bennett

12.03.24 - 06.04.24

Dorcas Tinamayi Biography:

“I was born in the bush at Wurturu rock hole near Kaltukatjarra (Docker River)”. After her birth, her mother and father walked with her to Warburton Mission where she was given her English name by the missionary Mr. Will Wade.

Her parents returned, walking with Dorcas to the Warakurna - Tjukurla area. Although soon after they had to leave due to the radiation exposure from the atomic testing in Maralinga “the funny smell made a lot of people sick”. Her family met Mr. Bob McAuley and traveled with him in the renowned yellow Native Patrol Officer’s truck to the Amata settlement. They then travelled by camel to Areyonga where Dorcas began to attend school.

Dorcas and her family returned to the Warakurna homeland when it was established in the mid-1970s. “In 2005 we started painting on paper then on canvas, the old shop turned into an art centre, that’s where we all started doing painting” Dorcas is the current Chairperson for Warakurna Artists. Dorcas Bennett is the daughter of Nyurupayia Nampitjinpa (Mrs Bennett) a senior artist for Papunya Tula Artists. Dorcas’s paintings are prefigured by her mother’s Tjukurrpa (dream time), encompassing the country between Tjukurla and Warakurna.

As the final heir to these ancestral stories, it is crucial for Dorcas to reenergizes them. She does so with a lot of gusto, creating vibrant connections between the dotted Tali (sand hills), the circler Kapi Warnanpa (water holes), and various designs linked to the journey of a group of women to the rockhole site of Yumarra.

ARTWORKS:

enquire.

JAMES CLAYDEN : THOUGHT / MEMORY PAINTINGS

James Clayden

30.01.23 - 02.03.24

Jame clayden: artist statement

Early in 2023 after rewatching Peter Weir’s fantastic film The Last Wave I found myself once again disappointed with the way the film ended and thought to try and paint an ending for myself. The thought kept going around in my head and began merging with the memory of being in the Lisbon Aqueducts that were built on ancient Roman structures during the 18th century; this seemed together with the feeling left by the ending of the film, of being underground beneath the city but at the same time in some deep space far beyond, where past and present pulsed like some atavistic memory of longing amidst water and sky like spheres as one. Out of this, I remembered Michael Snow’s haunting 1967 short experimental film Wavelength and after watching it again it seemed something worthwhile was going on around me, without me, and this together with the mystery of painting itself is more or less how and why I began work on this series of Thought/Memory Paintings.

ARTWORKS:

enquire.

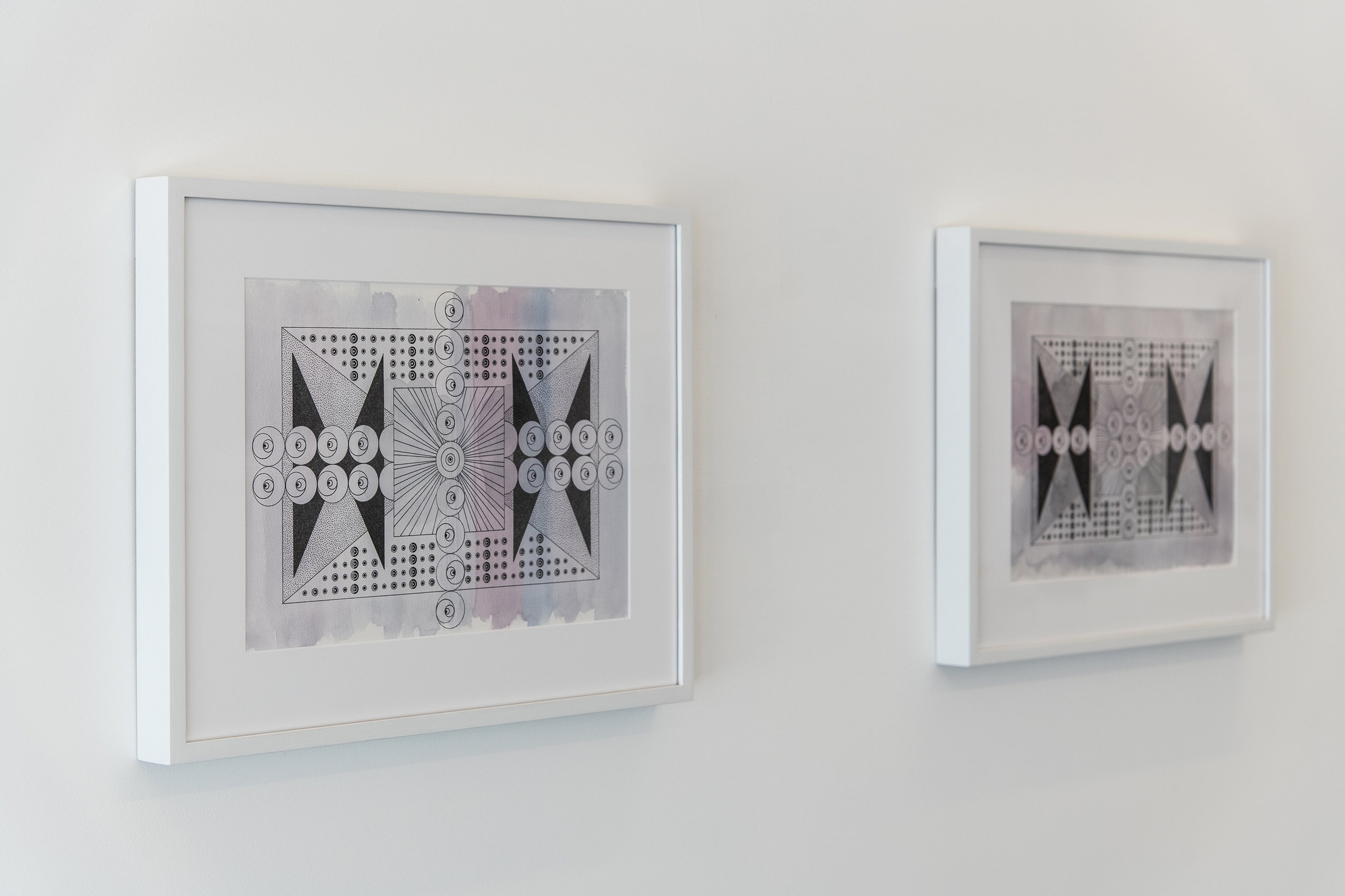

steven asquith: analogue pictures

Steven Asquith

21.12.23 - 27.01.24

Steven Asquith / analogue pictures

As a sequence of hieroglyphs that line the gallery walls, Steven Asquith’s new series of works on paper, Analogue Pictures, represent abstract narratives that attempt to unravel the current global diaspora and the circumstances and events affecting us all today. But unlike the ancient hieroglyphs that depict a literal representation of events or stories, the imagery in Asquith’s works forms an abstract language and gestures to our inner response to the events of today and our recent past.

Analogue Pictures continue Asquith’s exploration of abstract narratives that engage with psychological states derived from contemporary narratives. The layered and intricate works are fine representations of Asquith’s concern with the multi-layered meanings that images encompass. A point of departure in this enquiry is the numerous definitions of the term analogue in the exhibition's title.

Analogue can signify the information or signals represented by a continuously variable physical quantity such as spatial position; a contrast to the digital and technology; signify a person or thing seen as comparable to another; a clock or watch showing the time by means of hands or a pointer rather than displayed digits; analogue sound machines; repetitive patterns. In Chemistry, an analogue is a compound with a molecular structure similar to another. We can consider an analogue to be something similar or comparable to something else, in general, or in some specific detail—something analogous to something else. These varied connotations suggest a polysemous lens with which we should approach these works.

At first glance, the series of 20 works on paper seem identical. However, upon closer examination, we notice the restrained variances in each. Take for instance, the watercolour underlay in each work. Each portrays contemporary skyscapes affected by smog or cloud formations at urgent times of the day. Here Asquith alludes to the traditions of the landscape, although these are rendered with an allusion to the real threat of global warming and climate change. The epoch of these works is contemporised in reference to the most significant issue affecting humanity's future: our reliance on fossil fuel economies and that our dependency needs to be addressed. Fast. And although this observation is apparent, it is only one of the many implications of the work.

Next, we look to decipher the other abstract icons in the works. Familiar abstract tropes and shapes —squares, triangles and circles—reveal diverging patterns across the surface of the works. How they are composed and repeated allows us to grasp the differences.

Abstractions resonant of eyeballs appear to rush across the surface of the works at speed and in patterns, each more abstract than the last. Vertical and horizontal compositions emerge. At times circling out from the centre of the image, appearing as a sacred space meditation mandala. However, these meditations are present as a spiritual reconning of our age, influenced by the tension and turmoil of our post-pandemic consciousness. Here Asquith also uses these icons as metaphors for perception, with varied patterns suggesting differing interpretations of current events and outcomes.

The infinity centre of each work infers that the epicentres are collapsing in on themselves, perhaps as a portal to another dimension or a star collapsing in on itself at the end of its life. This presented phenomenon forms a central focus of the picture plane, directing the viewer's gaze and imagination to the possibilities contained within the images.

Within the bounds of the wavering compositions, the viewer’s gaze continually returns to the eyeball at the centre of each image. Functioning as an axis, it guides the viewer to the midpoint of the image and engages them directly – always staring back. A centripetal counterpoint to the unease and disarray of the darting eyes surrounding it. The eyeballs evoke different patterns for how we respond to our environment and perceive threats of our time.

We then look to the menacing dark triangle formations that sit as guardians on either side of the collapsing infinity centre of the work. Ominous and with sharp edges, they lurk and threaten to slice the eyeballs as their patterns emerge across the picture plane. One thinks of the surrealist film Un Chien Andalou, the 1929 French surrealist film directed by Luis Buñuel and written by Buñuel and Salvador Dalí, in reference to the inferred horror and present danger these sharp-edged triangles appear to present. When Buñuel is about to slice the young woman's eyeball with a razor, she stares straight ahead as he brings the razor to her eye. The scene then cuts to an image of a cloud passing before the moon. In Asquith’s images, these menacing triangles hover and threaten to glide and sliver the eyeballs across each image at any moment.

The only variances within the repetitive compositions are the patterns of eyeballs and skyscapes that change and differ in their symbolic relationship with one another. The tropes are presented with the direction for the viewer to decipher and derive meaning from the abstract narrative. As if these works say everything and nothing simultaneously—the viewer is asked to interpret these messages and feel the response as they are present in front of the works.

Each work represents our collective physiological response to the events of our recent past—the inner world of our being. The abstract narratives portray internal responses to external incidents—lockdowns, #BLM, economic instability, destabilisation of the Asia Pacific region, the digital, our imminent environmental collapse, fossil fuels, [insert your own inescapable disaster here].

Within the convolutions of the narratives within these works, Asquith presents a dichotomy between the washed watercolour backgrounds and the sharply rendered abstractions that float above like architectural drawings for concepts yet to be fully grasped. The crisp line work contrasts the soft painterly qualities of the backgrounds, yet somehow, they are co-dependent to balance and resolve the works. Two languages and techniques are at play here, each desperate to find a voice, yet each is utterly meaningless without the other.

By Dr Aneta Trajkoski, University of Melbourne

ARTWORKS:

enquire.

KYLE JENKINS: CELARE PAINTINGS

Kyle Jenkins

10.05.23 - 17.06.23

KYLE JENKINS / CELARE paintings

The monochrome was first created in the late 19th Century by Paul Bilhaud and his work Combat de Nègres pendant la nuit ("Battle of negroes during the night") 1882, however historically its establishment as a painting strategy is in early 20th century Modernism with Kasimir Malevich’s ‘Black Square’ 1915. This marked a point of departure in painting that has been readdressed by numerous artists, movements, and groups since 1950s, such as European abstraction, Swiss Concrete, and New York Neo-Geo. Historically a monochrome can suggest the removal not the application of paint because there is no identifiable representational image in the work. This is incorrect because these forms of work are not reductive as they aren’t about taking something away, it is about maximising and focusing on what’s there.

For myself, what the monochrome (and my work) investigates are active tropes associated with the very act of painting in both historical and contemporary contexts. Instead of figuration and recognisable images (representing objects/scenes/feelings in art), this work is about non-figurative propositions that engage with history, the marketplace, and the way in which a painting is received in the early 21st century. The word Celare(the title of these paintings) means to colour, to cover, conceal, destroy, and hide. This series of misshapen monochrome works deal with issues of originality (appropriation), authorship, presentation, display, and the act ‘of painting’ where the actual picture in the painting is the painting itself. Additionally, by creating a monochrome, one is engaging with the history of such painting but also the problems every person is dealing with when making a painting, that of the problems of colour, shape, composition, weight, tonal value, scale, flatness, the frame of support. Instead of adding and adding, these aesthetic issues are just all collapsed into one colour, one surface, one composition, one construction, as one painting, that is about questioning what painting is, and could be. The monochrome works are about encoding each painting with the very nature of what painting is re: production, perception, reception, and interpretation. In this way what you bring to the work is what you get from the work because the paintings aren’t about creating illusion based within the technological or representational screen but is about looking back at the viewer offering a sense of reconciled finality through colour relationships and formal limitations.

The CELARE monochromatic paintings are about engaging with the tradition that the reading of a painting is all about its surface; as such, this series of shaped-based canvases can seem to mimic architectural motifs, but also exist in a space between painting and object, creating a tension that asks, “is it a painting, is it an object or ultimately what is it as an artwork?” One of the ways this is done is by creating paintings where the edges are imperfect, with a hand-made DIY aesthetic. The sides of the canvas are painted so the work acts as a surface of intention indicating that the function is tied to its tradition, but the artwork also becomes a painting ‘as’ object. In these works, the main conceptual premise is how far can you push the creation of a painting, or the traditional notion of a painting, before it dissolves into being read as an object, architecture, design, or nothing at all. Ultimately these paintings confront the traditions of painting into a tensity between art and non-art, existing within authorship, the monochrome, painting ‘as’ object, architectural motif and the everyday.

The works are constructed through a process where wood is hand cut, not measured or ruled up, allowing the intuitive construction and slight wobble in the form’s edge to be left as a sign of construction. The wood panels (that have canvas stretched over them) are associated with topology, a subdivision of geometry, which deals with characteristics of geometric figures that are preserved despite certain deformations. These occur in the frame’s edge, not its field. The tension between this creates a form of construction that appears miss-constructed where the un-level, un-square, warped edges are the structural parameters of the painting but are also falling out of the paintings frontal field over the edges through its application of paint. In these paintings, the edge becomes an act of divergence where small changes in the edge of the frame (the traditional notion of what a painting frame is, its geometry and structure as a square or rectangle) is challenged and these works are as much about what is outside the frame as within.

The series of misshaped panels challenge the notion that the reading of a painting is all about its surface; as such, by juxtaposing one paintings scale to the next creates a multi-reading within the paintings collectively, where the viewer can read each painting potentially as a coloured void and/or object in relation to the wall that it’s located against, considering the work in relation to the architecture that the work exists within; or considering the tonal weight of the colour/s used singularly and collectively. The relationship of the shape of the painting to the wall and the room creates synergetic notions of space where the physicality of it, the paintings shaped space (as both surface field and as object) and the remainder of the exhibition space, combines as transitional units. In this sense the shaped paintings are not autonomous units, instead, they are composed of the painted-shaped frame placed on the wall together with its negative, the space sitting outside its edge. Within this there is a relationship between frame construction, tonal presence and space, and the parallel relationship of painting, space, and viewer. The paintings are not just about responding metaphysically to the works in terms of colour, line, and scale, but are also about the angle at which the viewer is standing to the work, their position within the space and the positions of the other works within this same space.

Artist Statement, 2023

WHAT YOU SEE IS YOU

When an artist is asked what kind of paintings, they ‘make’, it is in the response where initial interpretation is key to providing visual answers. For the landscape, figurative, abstract or portrait artist, there is an instantaneous visual connection; whether the genre is agreeable to the viewer or not, an understood association is instantly established. For the monochrome painter, however, the answer can easily be misinterpreted as a kind of conceptualised notion of potential possibilities; a suggested idea of other, resulting in a sense of disconnect or possible unknown. For Kyle Jenkins, the answer is in the question, and the question is exactly what he’s challenging and bringing to the fore in this series of artworks.

For artists embarking on producing monochrome paintings, they’re aware it can never, not acknowledge its own history. Jenkins’ practice is engaged with collapsing historical and physical attributes of painting, such as shape, colour, composition, tone, and flatness into the one constructed object, to question the possibilities of what painting can be today. There are considered applications such as tonal value and crafted edges, that reflect his intended aesthetic and conceptual intentions, as well as an acknowledgement of artists before him, who investigated ideas including appropriation and authorship in relationship to the monochrome. What is timely though, about this exhibition and group of highly constructed monochrome paintings, is that Jenkins has intentionally made them to be viewed and engaged with by an audience in the third decade of the 21st century. Through their painterly application and physical presence, these CELARE paintings bring new ideas of authorship, absence, and appropriation, historically associated with monochrome painting, and confront notions of identity, simply by being painted in an era where our sense of self is challenged by a visual culture that’s saturated by an influx of digital imagery.

This digital culture provides information to be visually downloaded or subsumed via various mediums and devices that are rapidly distributed and automatically communicated, either as images, text, and or sound. In particular, when viewing images via digital technology, the screen appears to flatten potential edges and objects, at once offering up a seamless illusion whilst simultaneously preventing us from focusing on any one thing. This creates a strategy of withdrawal from ‘experiencing’ the full essence of the subject or image, in turn, limiting our perspectives of being in the world.

The speed at which we consume visual information via a screen, where one image from one time and place is collapsed on top of the next, combined with reduced details (materiality) of how an artwork’s physicality (such as brush marks, colour, tonal variations etc.), offers up delusions of photo-real impressions, creating false truths and disorientated understandings of reality. For monochrome painting, and the viewing of it through a screen, blocks of monochromatic fields appear to negate any suggestion of historical or conceptual narrative, reducing any DIY aesthetic qualities. When viewed in the gallery or physical space, monochrome paintings reveal their material details of construction. Additionally, the viewer is drawn into the work on a more intimate level, inviting them in to take a closer look, experiencing the artists ideas / paintings more personally. It is here that a level of presence in the works is negated by digital technology and a redirecting of the viewer’s focus away from the physicality of a painting’s construction, occurs. Any focus on painterly issues such as materiality, perception, production, and interpretation, are reduced, and when this occurs, so too are ideas and notions of the self.

In Jenkins’ CELARE works he uses the practice of painting to problem-solve associated issues related to colour, surface, and construction; a way of wearing his heart on his sleeve (so to speak), revealing potential struggles or organisational issues related to the manufacturing of the paintings. Issues such as colour placement, or dealings with edges and irregular forms, emphasising negative spaces between the works, considering the architecture, and exaggerating the picture planes flatness, are all ways for him to discover potential realities that look at the nature of painting and how far it can be pushed, or minimised, to reconstruct it. Jenkins questions ‘what is painting and how do we experience it’, through this interrogation, and as such an element of empathy is ignited in the viewer, and so too are new notions of truths and authorship.

All these painterly issues, both physical and conceptual, are so closely entwined with the genre of monochrome painting and are essential to being seen and experienced first-hand. Jenkins knows that potentially, most of the audience for these paintings will be viewing the work through a screen. He makes no apologies for this, and through his unwavering investigation, dares the audience to do the work too. They need to get in front of the paintings, and by doing so see beyond any false, digital seamless imperfections, into new perspectives and truths. These monochrome paintings mirror Jenkin’s authentic self, through their constructed nature and irregular physicality combined with intentional and considered details, they could be interpreted as self-portraiture, exposing his search for truth, that simultaneously offers room for his viewer to do the same, to bring us all back to really seeing and experiencing ourselves, through the work. It is in this way, the CELARE paintings act as a group of paintings that are collaborative in nature, whereby they offer ways for the audience to connect back with the physicality of themselves, the world around them, and each other.

Tarn McLean

Dr Tarn McLean is an artist, designer, and Doctor of Philosophy (Visual Art) and founded the Australian accessories and textile company Ocre Designs in 2008.